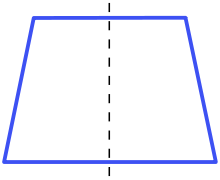

Isosceles trapezoid

| Isosceles trapezoid | |

|---|---|

Isosceles trapezoid with axis of symmetry | |

| Type | quadrilateral, trapezoid |

| Edges and vertices | 4 |

| Properties | convex, cyclic |

| Dual polygon | Kite |

In Euclidean geometry, an isosceles trapezoid[a] is a convex quadrilateral with a line of symmetry bisecting one pair of opposite sides. It is a special case of a trapezoid. Alternatively, it can be defined as a trapezoid in which both legs and both base angles are of equal measure, or as a trapezoid whose diagonals have equal length. Note that a non-rectangular parallelogram is not an isosceles trapezoid because of the second condition, or because it has no line of symmetry. In any isosceles trapezoid, two opposite sides (the bases) are parallel, and the two other sides (the legs) are of equal length (properties shared with the parallelogram), and the diagonals have equal length. The base angles of an isosceles trapezoid are equal in measure (there are in fact two pairs of equal base angles, where one base angle is the supplementary angle of a base angle at the other base).

Special cases

[edit]

Trapezoid is defined as a quadrilateral having exactly one pair of parallel sides, with the other pair of opposite sides non-parallel. However, the trapezoid can be defined inclusively as any quadrilateral with at least one pair of parallel sides. The latter definition is hierarchical, allowing the parallelogram, rhombus, and square to be included as its special case. In the case of an isosceles trapezoid, it is an acute trapezoid wherein two adjacent angles are acute on its longer base. Both rectangle and square are usually considered to be special cases of isosceles trapezoids,[1][2] whereas parallelogram is not.[3] Another special case is a trilateral trapezoid or a trisosceles trapezoid, where two legs and one base have equal lengths;[1] it can be considered as the dissection of a regular pentagon.[4]

Any non-self-crossing quadrilateral with exactly one axis of symmetry must be either an isosceles trapezoid or a kite.[5] However, if crossings are allowed, the set of symmetric quadrilaterals must be expanded to include also the crossed isosceles trapezoids, crossed quadrilaterals in which the crossed sides are of equal length and the other sides are parallel, and the antiparallelograms, crossed quadrilaterals in which opposite sides have equal length. Every antiparallelogram has an isosceles trapezoid as its convex hull, and may be formed from the diagonals and non-parallel sides (or either pair of opposite sides in the case of a rectangle) of an isosceles trapezoid.[6]

Characterizations

[edit]If a quadrilateral is known to be a trapezoid, it is not sufficient just to check that the legs have the same length in order to know that it is an isosceles trapezoid, since a rhombus is a special case of a trapezoid with legs of equal length, but is not an isosceles trapezoid as it lacks a line of symmetry through the midpoints of opposite sides.

Any one of the following properties distinguishes an isosceles trapezoid from other trapezoids:

- The diagonals have the same length.[3]

- The base angles have the same measure.

- The segment that joins the midpoints of the parallel sides is perpendicular to them.

- Opposite angles are supplementary, which in turn implies that isosceles trapezoids are cyclic quadrilaterals.[7]

- The diagonals divide each other into segments with lengths that are pairwise equal; in terms of the picture below, AE = DE, BE = CE (and AE ≠ CE if one wishes to exclude rectangles).

Formula

[edit]

Angles

[edit]In an isosceles trapezoid, the base angles have the same measure pairwise. In the picture below, angles ∠ABC and ∠DCB are obtuse angles of the same measure, while angles ∠BAD and ∠CDA are acute angles, also of the same measure.

Since the lines AD and BC are parallel, angles adjacent to opposite bases are supplementary, that is, angles ∠ABC + ∠BAD = 180°.[7]

Diagonals and height

[edit]The diagonals of an isosceles trapezoid have the same length; that is, every isosceles trapezoid is an equidiagonal quadrilateral. Moreover, the diagonals divide each other in the same proportions. As pictured, the diagonals AC and BD have the same length (AC = BD) and divide each other into segments of the same length (AE = DE and BE = CE).

The ratio in which each diagonal is divided is equal to the ratio of the lengths of the parallel sides that they intersect, that is,

The length of each diagonal is, according to Ptolemy's theorem, given by

where a and b are the lengths of the parallel sides AD and BC, and c is the length of each leg AB and CD.

The height is, according to the Pythagorean theorem, given by

The distance from point E to base AD is given by

where a and b are the lengths of the parallel sides AD and BC, and h is the height of the trapezoid.

Area

[edit]The area of an isosceles (or any) trapezoid is equal to the average of the lengths of the base and top (the parallel sides) times the height. In the adjacent diagram, if we write AD = a, and BC = b, and the height h is the length of a line segment between AD and BC that is perpendicular to them, then the area K is

If instead of the height of the trapezoid, the common length of the legs AB =CD = c is known, then the area can be computed using Brahmagupta's formula for the area of a cyclic quadrilateral, which with two sides equal simplifies to

where is the semi-perimeter of the trapezoid. This formula is analogous to Heron's formula to compute the area of a triangle. The previous formula for area can also be written as

Circumradius

[edit]The radius in the circumscribed circle is given by[8]

In a rectangle where a = b this is simplified to .

Duality

[edit]

Kites and isosceles trapezoids are dual to each other, meaning that there is a correspondence between them that reverses the dimension of their parts, taking vertices to sides and sides to vertices. From any kite, the inscribed circle is tangent to its four sides at the four vertices of an isosceles trapezoid. For any isosceles trapezoid, tangent lines to the circumscribing circle at its four vertices form the four sides of a kite. This correspondence can also be seen as an example of polar reciprocation, a general method for corresponding points with lines and vice versa given a fixed circle. Although they do not touch the circle, the four vertices of the kite are reciprocal in this sense to the four sides of the isosceles trapezoid.[9] The features of kites and isosceles trapezoids that correspond to each other under this duality are compared in the table below.[10]

| Isosceles trapezoid | Kite |

|---|---|

| Two pairs of equal adjacent angles | Two pairs of equal adjacent sides |

| Two equal opposite sides | Two equal opposite angles |

| Two opposite sides with a shared perpendicular bisector | Two opposite angles with a shared angle bisector |

| An axis of symmetry through two opposite sides | An axis of symmetry through two opposite angles |

| Circumscribed circle through all vertices | Inscribed circle tangent to all sides |

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ The name trapezoid is from American English. Alternative name known as isosceles trapezium in British English. See the difference between trapezoid and trapesium.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Alsina, Claudi; Nelsen, Roger (2020). A Cornucopia of Quadrilaterals. Mathematical Association of America. p. 90.

- ^ Wasserman, Nicholas; Fukawa-Connelly, Timothy; Weber, Keith; Ramos, Juan; Abbott, Stephen (2022). Springer. p. 7. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-89198-5. ISBN 978-3-030-89198-5 https://books.google.com/books?id=0ppXEAAAQBAJ&pg=PA7.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ a b Ryoti, Don (1967). "What is an Isosceles Trapezoid?". The Mathematics Teacher. 60 (7): 729–730. doi:10.5951/MT.60.7.0729. JSTOR 27957671.

- ^ Alsina & Nelsen, p. 100.

- ^ Halsted, George Bruce (1896). "Symmetrical Quadrilaterals". Elementary Synthetic Geometry. J. Wiley & sons. pp. 49–53.

- ^ Whitney, William Dwight; Smith, Benjamin Eli (1911), The Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia, The Century co., p. 1547.

- ^ a b Alsina & Nelsen, p. 97.

- ^ Trapezoid at Math24.net: Formulas and Tables [1] Archived June 28, 2018, at the Wayback Machine Accessed 1 July 2014.

- ^ Robertson, S. A. (1977). "Classifying triangles and quadrilaterals". The Mathematical Gazette. 61 (415): 38–49. doi:10.2307/3617441. JSTOR 3617441.

- ^ De Villiers, Michael (2009). Some Adventures in Euclidean Geometry. Dynamic Mathematics Learning. pp. 16, 55. ISBN 978-0-557-10295-2.